Chapter 1. The Untold History of the World

Introduction and a Short Summary

of this Chapter

Section 1. Creation, Original Peoples (Satyug,

0-15,000 bp)

Section 2. The Coloniser (Kaliyug,

15,000-500 bp)

(More Details) Peasant Culture,

Mind-Control and Language History

> Section 3. Gurmat, the Guru’s Teachings

(In Kaliyug, 5,000-Present)

A Short Summary of this section

(Part 1)

Ancient Wisdom Restored

> (Part

2) Dharamshalas

and Restored Indigenous Culture

EXCLUSIVE! An illustrated history of the Guru’s Dharamshalas

(Part 3) Khalsa

Restoration and Challenges

(Part 4) Truth-telling: “Sikhism”, the False Religion

Section 4. The ‘Modern’ Age (Kaliyug

Nadir, 500 bp-Present)

Section 3. Gurmat, the Guru’s Teachings (In Kaliyug, 5,000-Present)

This Section details the history of Gurmat and the story of our Aboriginal ancestors, the Guru, and their Sevaks, including the sacred Origin and their struggles to restore Original Wisdom in the face of genocide and Colonisation. Following a short summary, it is divided into four parts. Please read each part in turn.

A Plea to “Sikhs”: You will find this genuine history of Gurmat to be very different to the many lies that you have been fed by the Patriarchal owners of “Sikhism”. The few well-meaning and misled Gurmukhs out there will however resonate with this truth in their heart, owing to their love for the Guru.

Part 2. Dharamshalas and Restored Indigenous Culture

For the first time ever, we are excited to present an exclusive illustrated account of the Humble, Natural and Sacred lifestyle of Sevaks and material culture at the Guru’s Dharamshalas c.500-300 years ago. Take your time to visualise this other world, where time stood still and lions and elephants roamed freely. Importantly, this sacred Akaal Jeevan (timeless natural existence) is a living story (that will be told in Chapter 2). Note: More illustrations will be added soon.

The Guru Matas (women Gurus) nurtured Gurmat by creating Dharamshalas (places of refuge and learning) throughout the Colonised world, as beacons of Original Wisdom, where they practically restored Indigenous culture. These decentralised, self-sufficient and sustainable, egalitarian forest-villages consisted of a shared communal life immersed in Original Wisdom, with Grandmother Elders in charge of everything as a Matriarchy. Community members spent all their time in Nishkam Seva (selfless service), Kudrati Jeevan (a natural life at One with Air, Water and Earth), and Adhiatmik Dhian (sacred song, ceremony and meditation); existing as humans were created to be. Dharamshalas gave an opportunity to people from all backgrounds to become Sevaks (lifelong humble servants and disciples of the Guru) and serve their Elder Relatives- Air, Water and Mother Earth, thus fulfilling the Original Agreement. Centred on the Humble, Natural and Sacred, the lifestyle of Sevaks at the Guru’s Dharamshalas was completely different to that in the Colonised world. Through Humble service, Sevaks could re-gain Nimrata (Deep Humbleness), the Heart of the human being; and hence de-colonise. And through practical immersion in Original Wisdom, including a Natural life in harmony with Mother Earth and Oneness, and though ancient Sacred practice- they could re-Indigenise as Khalsa (natural humans). Protecting Mother Earth, nurturing Nimrata and re-training as a human being were the most important functions of the Dharamshala. They restored natural harmony and paved the way for the rise of a New People from all four directions, as per the Khalsa Prophecy (instruction).

Grandmother Council

Dharamshalas were created by the Gurus by finding and emancipating millions of acres of land from Coloniser ownership (enslavement)- usually donated by villagers or local rulers, and then finding and enlightening Humble Sevaks and Elders to live there in eternal service as Sadhsangat (awakened-community). First, the Guru Matas healed the land from the wounds of Colonisation with sacred ceremony and replanted forests. Then the Matriarchs starting with Guru Mata Nanaki, restored the ancient Indigenous culture of the Black Aboriginal Tribes whose sacred territory the Dharamshala was being created on, working respectfully with local tribes where they existed, and through divination. This included Aad-Samvaad (sacred Indigenous song and ceremony), food, crafts, clothing, art, architecture etc. Each aspect of this restored ancient Indigenous culture and lifestyle carried important sacred Indigenous wisdom, honoured sacred Aboriginal Cosmology, and reflected the vital relationships with our Elder Relatives- Air, Water and Mother Earth. In this way ancient Indigenous culture as per the local geography was fully restored, and Naam (divine-centring energy) once again radiated and harmonised the land.

Being One with the local geography, flora, and fauna, were critical to the Sevak’s identity, and were reflected in spiritual namesakes, totems and honouring of local sacred sites. Along with the horse, eagle and other sacred beings, Guru’s Sevaks had a special relationship with Big Cats (Lion/tiger/leopard/panther/lynx etc) as their primary totem and namesake: they were divinely gifted with an Indigenous identity as Singh’an, a Big Cat People; duty-bound to honour and serve Big Cats, and Dharamshalas protected Big Cat territory. Sevaks thusly had a vociferous identity as a Matrilineal Spiritually Indigenous People. For children born and raised there and initiated by the Elders, this restored Indigenous identity was permanent and indelible, thus fulfilling the Khalsa Prophecy (instruction), for a New People to arise who will help heal and restore the world. There was also a great mutual love and support between the Guru Matas and Sevaks, and local Aboriginal Tribes, who would regularly visit and stay at the Guru’s Dharamshalas, and vice-versa. They were great allies and their intimate relationship reflected an ancient divine Aboriginal kinship. Meanwhile, the likes of kings, landlords and businessmen were spurned if they came to flaunt their wealth and fame; Dharamshalas were a refuge for the Humble.

Dharamshala society was entirely communal, with no individual family units; all families, directly related or not, were part of Sadhsangat (awakened-community) as a spiritual family. Indeed children were raised communally by the whole village. Sevaks were also organised into Matrilineal clans (emphasis on the female line), each honouring different animal and plant totems. Clan Grandmothers became Matriarchs; and men, being members of Matrilineal clans, greatly revered them and served women with humbleness. This ensured harmony in society and with Mother Earth, as per Original Wisdom. Decision-making was by consensus; Elders would gather in council, sitting in Sacred Circle-led and facilitated by Matriarchs. Major issues required spiritual quests and ceremony and the Grandmothers would pronounce Hukamnama (sacred guidance) after communing with the Aad Guru and the Elder Relatives. Marriages were arranged by the Elders, and sex and birthing served a sacred and communal purpose and were all conducted with the guidance of meditating Grandmothers. The birth of a girl (a future Matriarch) in particular, was celebrated with much fanfare. Babies were carried wrapped close to the body by women as they worked, constantly singing sacred song to them. Indeed birthing and raising children into Original Wisdom, was absolutely essential and the foundation of Dharamshala life; to create community, forge Indigenous identity and thus fulfil the Khalsa Prophecy. Women took their sacred mandates as creators and teachers of life, and crucibles of Nimrata, very seriously indeed, and there was a continuous aura radiating from enlightened mothers and babies.

Children began learning skills and were trained in their sacred mandates from birth, with even lullabies and games being rooted in the sacred. They didn’t learn at a school; they explored Earth, learned real wisdom from Elders and did their share of communal tasks, thus learning on-the-go. By the time children reached adolescence, they were fully trained in their sacred mandates and practical responsibilities and were allocated a lifetime of communal work (no single profession) by the Elders, culminating in rites of passage to adulthood. Raised with Sanskar (cultural values), such as respect for Elders and the sacred; there were no teenage ‘rebels’. They developed a very strong self-identity with their culture through storytelling, meditation, language, arts and crafts and Raag Keertan with traditional instruments. All were taught to communicate with Air, Water and Earth and some were selected by divination and trained by the Elders from an early age- for a lifetime of sacred responsibility and duty.

Mothers and babies

At Dharamshalas, money, industry and commerce were considered to be vile. The community was fully self-sufficient; people made everything they needed by hand using traditional crafts. There was no profession, no rich or poor - everyone served communally as directed by the Elders and everyone was equally valued. Daily communal tasks were not seen as mundane chores; they served critical sacred functions and Sevaks pitched in enthusiastically. Some specialist tasks required expertise as knowledge-keepers- a responsibility, not a profession. Some tasks were gender-based; fulfilling their sacred mandates, women honoured Water and were crucibles of Humbleness; birthing, gardening and spinning. Men kept Fire; literally chopping wood and serving women with Humbleness. Together, they served Mother Earth and breathed the sacred Mantras to honour Air. Indeed, everyday-life was simple, beautiful and slow-paced; with some work (as Nishkam Seva- selfless service), some spiritual creativity (within a Kudrati Jeevan- a natural life) and plenty of Adhiatmik Dhian (sacred song, ceremony and meditation), all done collectively and for a greater purpose- as directed by the Elders. These three Humble, Natural and Sacred functions necessarily occupied the whole day and all of the community’s thought and dedication. Working communally, life was also very flexible; communities spent as much time as needed on their fundamental duties, e.g. several months or years honouring and protecting a river or travelling to a sacred site, without having to worry about income, food, housing etc. Sadhsangat (awakened-community) took care of everyone’s needs.

With the Elders deciding whom to marry, and what work to do (based on divination), life for Sevaks became simplified and stress-free. People did not think too much, plot, scheme, manipulate, or exercise the false intellect. This allowed them to focus their mental energies towards the important things in life, such as fulfilling Seva, being creative, engaging with nature, meditation and teaching children culture; a communal life did not prevent creativity, rather it was much enhanced. People felt greatly blessed and thankful for the Sahej, an intuitive, natural existence, and the resulting Anand, great spiritual bliss. Together with humble service, this simple-mindedness nurtured Nimrata, Deep Humbleness, the Heart of the human. Indeed Nimrata, was the most important part of Dharamshala life, and manifested itself in people’s body language and behaviour: Sevaks walked barefoot, squatted to rest, sat cross-legged, and ate by hand; because this is how Nimrata naturally manifests (an Egoistic person reaches for a chair and cutlery). Behaviour-wise, people were minimalists, extremely content with their few possessions and humble lifestyle, and were in awe of the great gifts of Mother Earth. They intuitively thought and acted communally.

Indeed, the disease of individualism simply did not exist; all were equal in this communal system. There were no individual aspirations or wants, and people did not have, nor ever want any private space, property or solitude. There was no discord, and people eagerly worked for the communal good; it was perfectly natural and normal. Private ownership just did not exist and Sevaks could not fathom why anyone would burden themselves with collection of the material. People saw the outside world, with its individualism and thus, anger, violence and rape- as unusual, strange and foreign. They would ask Colonised visitors, manifesting Ego and unable to function normally (collectively): “Why would you live this? What’s wrong with you? Are you mentally unstable?” The Elders would respond: “Be compassionate! They are impoverished; they do not have the Heart [Nimrata]! Mother will heal them here!” People would collectively nod, fold their hands and murmur approvals “Sat Naam! That is how it is!”, as they often did when such a wise observation was made.

Adhiatmik Dhian (sacred song, ceremony and meditation) was an essential part of daily life. Gurbani (Guru’s sacred song) contains universal fundamental truths and instruction, primarily for the general Colonised masses to overcome their corruptions and re-orient themselves to the universal truths of Creator and the Original human existence. Aad-Samvaad (sacred Indigenous song and ceremony) was restored by the Guru Matas at Dharamshalas, to practically implement Original Wisdom, and to honour the seasons, celestial events, Grandmother moons, Grandfather sun, and the Elder Relatives- Guru Air, Father Water and Mother Earth. Aad-Samvaad and metaphysical communication also facilitated intimate relationships with the local geography and Elder Relatives, which was essential to the Sadhsangat (awakened-community). Sacred song was the life breath of Sadhsangat; throughout the day people would gather to sing, from honouring the sunrise, to evening Keertan (sacred song with celestial music) and on occasion, the drum was beaten and the conch was blown. Wild birds and animals joined in with the song and ceremony. The instruments used reflected these vital relationships with Elder Relatives, and were considered to be very holy; the voice and flute representing Guru Air, the string instrument and rattle representing Father Water, and the drum representing the heartbeat of Mother Earth. This singing and music invoked Naad vibrations, a universal celestial language that speaks directly to the spirit.

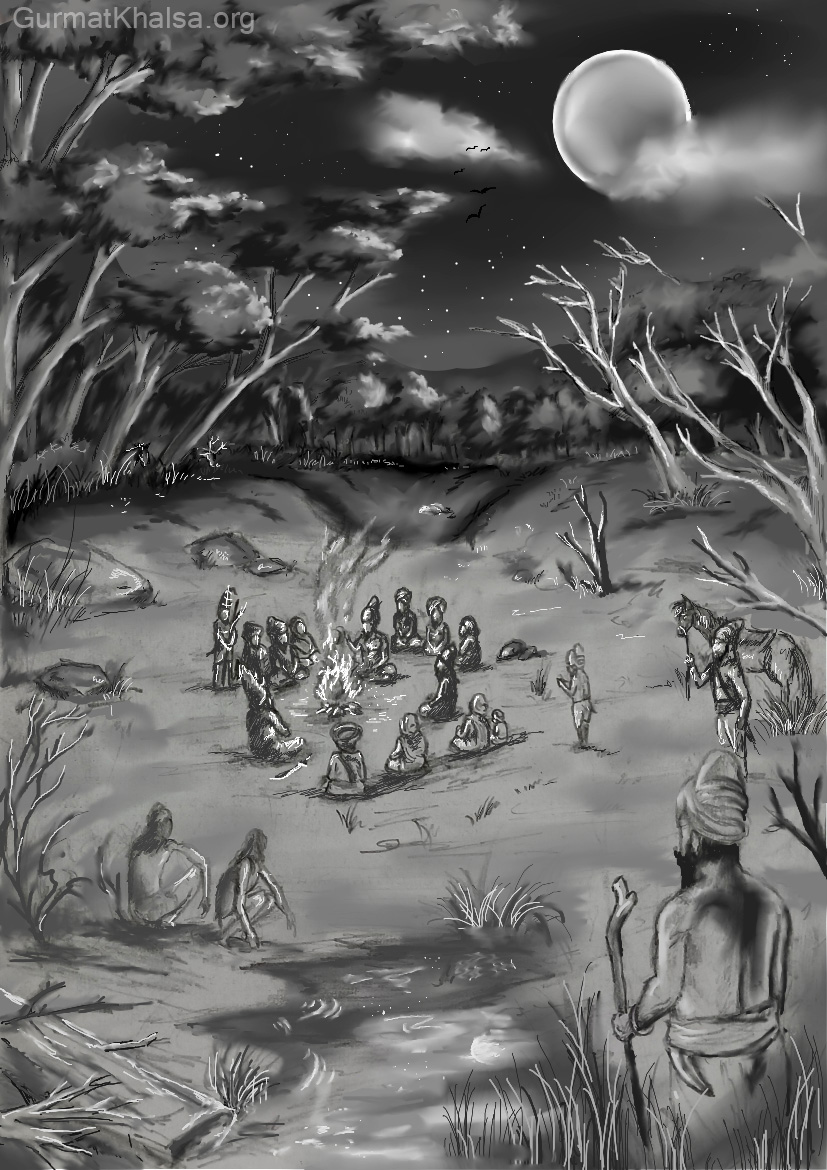

Keertan in the Jungle

Sacred rhythm in the community was continuous; even whilst performing everyday tasks, the Sadhsangat, often sang and danced in harmony. Indeed there was a sacred rhythm to everyday life, from the beating of the pestles in large mortars (to make flour), to weaving of cotton on backstrap looms, and even in the way people walked (gracefully in groups) and talked (melodiously); forming a symphony. This sacred rhythm and melodic symphony of everyday life was a hidden but very critical and profound facet of Original Culture. They weren’t merely sounds of village life; this Anhad Vaj (continuous sacred rhythm and melodic symphony) invoked metaphysical energies that regulated life and human behaviour. Thus all the daily life activities at a Dharamshala were essential, well-coordinated, and served important sacred functions.

Ancient sacred village rhythm

The rhythm of life was also attuned to natural cycles including seasons, planets, sun and moon. People swayed with the lunar cycles; at any time they intuitively knew the current phase of the lunar calendar, and women’s menstrual cycles were lunar-synchronised. The full moon and lunar events were honoured with special ceremony. There was no clock-time. The day was broken into eight periods (varying in duration with season), with people’s mental and physical energy coordinated with the sunrise and sunset. Every day without fail, people would gather together for a few hours before sunrise for Amritvela, a collective meditation, gradually vibrating their mental energy up from rest, to an active state. During the day, people were continuously meditating or singing whilst performing their tasks, but much of the day was spent honouring the silence and sounds of Air, Water and Mother Earth, including in collective ceremony e.g. listening to rivers, waterfalls, wind, birds and animals and insects. At dusk, people would slow down their body and mind, heading into evening prayer and Keertan, and then further into rest and deep meditation, which continued during the dream-state; resulting in a 24 hour non-stop meditation with a rhythmic cycle.

In coordination with these natural cycles, people gathered in regular ceremony at the sacred Fire for dance, meditation and prayer. Sacred dance was very critical to Dharamshala life- and celebrated the natural and sacred (not hedonic). Dressed in colourful ceremonial costume with sacred symbolism, women and men would sing and dance in circles and would beat the drum, honouring all four directions. Through dance, Sevaks connected with the ancestors and spirits, and told the ancient stories of the land through their body movements. Thusly everyone was continuously and collectively in a sacred rhythm and meditation, at the macro and micro levels, which built a profound and enlightened life.

Sacred dance and ceremony

Water and sacred Fire were a very important part of life and ceremony. Spiritual initiation centred on Water ceremony, blessed by the Matas. Women, carriers of sacred (womb) Water, were entrusted with protecting and honouring Earth Water, which they did with significant fervour. Women leading ceremony at the river bank and waterfalls was a common sight, and they would walk together in rhythm carrying fresh water in earthen pots balanced on their heads (hands-free). Sacred Fire was always kept burning by Men, and has critical sacred importance as the Cosmic complement to Air, Water and Earth. Very importantly, Elders would travel to important sacred sites and vital Earth Nodes, throughout the region, to make sacred offerings, honour the ancestors and commune with the spirits- to harmonise the rhythm of the world, and bring forth healing. Sacred sites were off-limits to the general public and only Elders were permitted at Earth Nodes, which are human-free areas. Waterfalls were considered to be the most sacred of these sites, as the holy meeting place of Air, Water and Earth.

Water ceremony at Waterfall

Aad-Samvaad (sacred Indigenous song and ceremony) was the foundation of all honouring and only the sacred and natural was celebrated. As Singh’an, a Big Cat People, important ceremony honoured the Big Cats, who would emerge from the jungle to accept an offering by the Elders. The monsoon or rainy season was considered to be particularly magical- special activities were planned and people gathered under a large open-walled thatched gazebo to listen to the rain as a collective meditation. The old Pagan Coloniser festivals (typically celebrating the Agrarian calendar) were totally rejected as being vile, and the likes of birthdays and anniversaries were never celebrated. Dharamshala culture was therefore unique and rooted in the sacred.

Sacred Fire

Dharamshalas comprised reclaimed and restored Indigenous territory, where Mother Earth hosted humans in return for Humble and sacred service. In South Asia they spanned across millions of acres of pristine nature, thick jungles with ancient Banyan groves and large wildlife- elephants, lions, tigers, rhino etc. As a Big Cat People, Dharamshalas were designed to protect their territory. Individual Dharamshalas varied in size, from hundreds to many tens of thousands of acres, at least 90% being pristine - never to be disturbed by humans (unlike Coloniser settlements which quickly consumed and destroyed nature). When looked at on a map, the different Dharamshalas were connected like a spider’s web, with living wildlife corridors; streams, hedgerows and paths, along which animals could move freely and people could travel to transport excess produce and for seasonal migration between Dharamshalas. Situated not far from flowing water would be a small clearing, where a village was built around a sacred life-centre. This centre was very important; it was where sacred Fire was made and ceremony performed. There would often be a large sacred Banyan or Peepal tree here, under the shade of which people would gather to rest and sing. Communal housing surrounded the sacred life-centre, and forest gardens, orchards and a paddock for horses would be in the vicinity. There would typically be a pond for bathing and ceremony, and the Guru’s Nishan, a triangular white flag with no markings, was often flown as a mark of peace and to indicate that refuge and food was available here. A large open-walled thatched gazebo provided communal gathering space during rain, and treehouse guard posts dotted the periphery.

Communal housing and outbuildings varied from small thatched mud or bamboo huts, yurts and buried earth houses, to larger lodges- depending on the function and climate. They were ecologically built with local, renewable materials, open-plan, and very importantly, with sacred geometry (no straight lines or right angles and special design features to honour sacred Cosmology). Several families shared communal living space. In some cases, the mothers and children, and the men, had separate quarters, depending on the ancient local Aboriginal culture that the Guru Matas had restored. There were no dedicated bedrooms; people slept communally on the ground- outdoors when the weather permitted, and when indoors, the sleeping area would transform into a multifunctional work and living space during the day. There wasn’t any Colonised furniture (beds, tables, chairs, cupboards etc). Instead there were grass/rattan mats, simple shelves and cane baskets to store their minimal belongings. Lighting was by oil lamp and fire, and people would sleep and wake early, with the cycles of the season. Nagara (large drum) was beaten to call for people to gather and send coded messages to neighbouring villages, relayed through the forest. Cremation was a time for joy and spiritual celebration rather than one of mourning, and the winter season was a time for deep contemplation. Sevaks bathed and washed their clothing in the river or with a bucket, mostly without soap- e.g. with chickpea flour or mud as an exfoliant and wood ash as a de-greaser. Hair was considered to be very holy; washed with special herbs like Reetha (soapnut) and Shikakkai, massaged with oils, carefully combed twice a day with wooden combs, and fallen hair was collected and cremated as a deceased human would be.

Village life

There was only one communal cooking fire and only certain enlightened people were allowed to cook, doing so with prayer, song and blessing ceremony. A variety of methods were used, primarily stewing and steaming in large earthen and iron pots, roasting flatbread and pancake on a large iron plate, baking in clay ovens and sometimes slow-cooking food wrapped in leaves in buried pits. The wood burning clay stoves or open fires were situated at ground level and all cooking was done squatting or sitting cross-legged on a mat, situated indoors or outside depending on the season and usually during daylight hours only. Meals were hearty yet rustic affairs and the scent of the wood fire and rich aromatic herbs filled the communal area and created a festive ambience every day. Meals were served in wooden or iron bowls- all handmade on site. Cutlery such as spoons and forks were not used- people strictly ate by hand and drank directly from the bowl. Guru ka Langar, the community meal, was eaten slowly in silent meditation, in carefully chewed small bite-size chunks, sitting cross-legged in facing rows, on the grass or under the thatched gazebo. The hungry enslaved peasant masses from neighbouring villages came in droves to enjoy this hearty, free, community meal, eaten sat side-by-side; without prejudice of caste or wealth (racial discrimination and classism did not normally permit different groups to eat together).

Throughout the year, Sevaks would carry Dharamshala-grown rations and prepare Langar in the neighbouring villages. As such, Dharamshalas became widely known for Langar Seva, and the Guru’s Nishan, carried everywhere by Sevaks as they travelled, became a trusted symbol. The repute of Guru ka Langar, particularly it’s edification of social unity, caught the intrigue of even the ruling Mughal Elite who, breaking all social norms, sat with (the so-assumed) ‘untouchables’ to partake by hand in a humble meal, and were left humbled by the experience. Karha Prasad (sacred pudding) was prepared with great meditation a few times a year on special occasions, typically made from millet or rice flour, vegetable or coconut oil, natural fruit sweeteners (never sugar) and nuts. A great blessing, it was eaten in awestruck silence, squatting on earth in humbleness (never standing). In the summer, refreshing lemony fermented drinks with tangy seasoning would be enjoyed during frequent breaks, with herbal infusions in the winter months. Alcohol was forbidden. Fresh water was drawn from rivers and wells and stored in earthen pots. Considered to be holy and alive, water was never boiled, nor stored for too long. Utensils were scrubbed with wood ash, clay and sand by hand or with plant fibre sponge and people composted their faeces and kitchen waste in deep pits.

Critically, there was no plant or animal Agriculture, nor any extraction or manipulation of nature of any kind; all lived as servants and children of Mother Earth, who provided sustainable food, herbal medicine and raw material through foraging, forest gardening and respectful hunting. Sedentary Agriculture was seen as vile rape of Mother Earth. The women’s forest gardens were incorporated into the forest canopy, and were self-watering, self-fertilising and often self-seeding and perennial. Only the women, as creators of life, were permitted to sow seed and tend to the gardens. They did this with intense prayer and devotion, yielding a spiritual nutrition that bred Humbleness in Heart. When asked, women would laugh: “Men, grow food? Nothing would survive! They’re only good for chopping wood!” And so, men were tasked with the general labour, which they did with great gusto. The gardens were never permanent, and moved around the forest (and sometimes the entire village was relocated), so as not to ecologically deplete any one area.

The diet was de-colonised: Wheat, domesticated meat, dairy (including Ghee) and eggs were not consumed under any circumstances at Dharamshalas. The food eaten primarily came from foraging. Indeed the forests were an abundant wild garden and the women carried great knowledge of food and medicinal sources. Depending on the climate, jackfruit, wild starchy and oily roots and wild seeds such as millet, lake rice etc, were primary staples, along with a plethora of edible leaves, bark, flowers, nuts, berries and wild fruit. Honey and wax was ethically obtained from wild bee hives without destroying the nest. Foraging was supplemented by growing corn, beans/lentils, vegetables, culinary herbs, fruit and oilseeds, in forest gardens and orchards. With such great variety, diets were very diverse and healthy, and there was no crop failure due to drought or pests with this natural ‘permaculture’ system.

Foraging and women’s forest gardens

The most senior male Elders would occasionally look for naturally deceased animals in the forest for shelter, tools, leather and drum skin etc. Only if absolutely needed, they would hunt (honouring Indigenous teachings) for this natural need - never for the desire of meat. Langar was always vegan, so the hunted meat would be offered to lions in the jungle or consumed by Elders, who would then embody the spirit of the animal that had given its life. Only in the most Northern climates were Sevaks permitted to eat (hunted) meat- only when absolutely required for sustenance, and only if sustainable. The rare occurrence of hunting was required to be ethical, respectful and spiritually elevated and carnivores and totemic animals were never hunted. Guns, traps and nets were not permitted; bows and arrows, spears or bare hands were used. Prayers were offered to the animal’s spirit before and after the hunt and great care was taken to carefully carry the animal in woven baskets and to cremate their remains with special ceremony. Domesticated animals such as cattle, chicken, pigs, goats and sheep, were considered to be enslaved Relatives, and great efforts were made to free them and end this barbaric cruelty in Colonised communities.

Food was seen and eaten as medicine, and by eating healthily and living an active and stress-free life in harmony with Elder Relatives- Air, Water and Earth (who regulate health at a metaphysical level), there was no ‘lifestyle’ illness, and diseases were very rare. Cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, allergies, thyroid dysfunction, depression, myopia etc simply did not exist. As life was slow-paced and machinery was not used, life-altering accidents were very rare. People walked barefoot, squatted, got a full body workout through daily work, got plenty of sunlight exposure and had strong natural immunity including gut micro flora that naturally produced vitamin B12 (also amply present in the unboiled fresh water and organic soil). Everyone was built like an athlete and obesity did not exist. Needless to say, people led very healthy lives in body and mind, and often lived to a hundred with no chronic disease and pretty good health in old age. Matas treated minor issues like cuts, burns and inflammation with herbal salves. When people rarely did fall ill, they consulted traditional healers, practitioners of the Guru’s Ayurveda (traditional medicine inherited from Aboriginal Elders), which saw disease to be the result of internal imbalances of the seven elements, itself caused by an imbalance with the natural world. Everything being interconnected, sometimes the entire community needed to cleanse together, and great healing took place through collective meditation, communal ceremony, medicinal herbs and tackling the root cause.

It is noteworthy that contagious disease and pandemic did not develop at Dharamshalas (or in any Indigenous society for that matter). It is the product of Houmai, the Ego, and a corrupt and barbaric lifestyle- exclusively a Coloniser phenomenon. It was brought by diseased Colonising invaders, often on purpose as biological warfare to murder Indigenous Peoples and depopulate entire regions. Then like now, Elders cured such disease with prayer, herbs, and by restoring balance. Coronavirus is such a Coloniser disease, caused by the rape of Mother Earth, which the Elders are healing at the root level, by promoting Nimrata (the antidote to Ego) and healing the Coloniser’s imbalances with Mother Earth (more info at www.CoronavirusTruth.info). To help the external Colonised masses struggling through their many pandemics (such as smallpox), the Elders often healed many thousands by absorbing the disease onto themselves, thus sacrificing their own lives for humanity. Such was their renown for healing the ‘incurable' that even infamously ruthless Coloniser kings would travel to Dharamshalas and beg for medicinal cures.

Communal Ayurvedic healing

Bana (dress and appearance) was unisex and hand-woven, with a sacred and practical function. Young children wore no clothing in the warm season, with their long hair flowing or braided. Typical work dress in the hot season was simply a Kachera (loin cloth) and Keski, small loosely tied turban, with a Kamarkassa wrapped around the waist. Women walked bare-chested outdoors as the norm; to cover the breast was considered to be strange and unnatural. During milder weather, people wore a Chola (a short robe or sarong), and in winter they wrapped up with a shawl. Never were trousers worn; it was the mark of the Coloniser. All Sevaks carried a Hazooria, a cleaning cloth, on their shoulder (never around the neck), as a mark of their Humbleness. They would wear various sacred objects for spiritual reasons such as Kara (iron bangles) worn on both wrists, Kanga (wooden comb) inside the turban, and Kar’d (small iron knife) supported by a sash around the shoulder. In battle, a larger double-turban was tied, with throwing weapons embedded into it. In ceremony people would wear colourful woven sashes and shawls with sacred symbolism, and sometimes adorn themselves with body paint and feathers, but never permanent tattoos, unusual piercings, rings or jewels. Women would often wear colourful beads representing their (Matrilineal) clan identity.

Local plant fibres (cotton, linen etc) were preferred in warmer regions, along with wild yak wool and naturally-obtained animal hides and furs in colder parts, for blankets and moccasins. Khaddar fabric was hand-woven with prayer, rustic and hard-wearing, with natural (undyed) or earthy pastel shades (from natural dyes). The processing of fibres and dyes and hand-spinning and weaving, was an important communal activity, in which every one of all ages, took part every day. When meditating, resting or having a conversation, people would quickly reach for their drop spindles (carried at all times); it was a sacred act (and contributed to communal yarn). Natural and sacred Cosmological symbolism would often be represented as sacred motifs, block prints and patterns on clothing, ceremonial costume and textiles (bags, bedsheets etc). Weaving was mostly on backstrap and vertical (rather than square, rigid) looms, sitting on the ground. Women would weave their spiritual dreams onto rugs and tapestries, as sacred art that linked the Cosmological with the material, and the artwork and sacred technique was passed on from mother to daughter- considered to be very valuable sacred heritage. This provided ample opportunity for creative and sacred art and maintained knowledge of oral histories and matrilineal clans.

In places where it grew, the wild perennial cotton tree (e.g. Desi Cotton- Gossypium Arboreum) was considered to be very sacred. It grew in beautiful meadows and had great herbal and spiritual Medicine. As per the ancient Aboriginal Cosmology of the Punjab restored by the Guru Matas, Sacred Mother took the form of spider woman and wove the Earth using the clouds, which hung like cotton bolls in the sky. She then took the form of a cotton tree. To honour this was women’s sacred mandate; they would pick cotton with prayer and all generations from grandmother to young girl sat together in the beautiful meadows spinning, weaving and sewing, singing sacred songs of spider woman, and intensely channelling the divine feminine energy of Creation from their wombs, into the yarn and fabric. In doing so, they became spider women; they were One with Mother Earth and their energy radiated into society; invoking Humbleness, love and sharing. The tree, sky and womb were also sacred motifs represented on textiles and spiritual art. Importantly, the fabric thusly woven and sewn into Bana carried miraculous strength that famously protected Akaali warriors in battle, who became immune to arrows and swords; one had the strength of forty. Men were in awe and bowed to these spinning goddesses.

Spinning goddesses

In other words, the lifestyle and material culture at Dharamshalas was completely opposed to the Coloniser’s culture described in the previous Section. Needless to say this attracted the hate of Colonising barbarians, who were hell-bent on wiping out Dharamshalas, murdering the Elders and extinguishing Aboriginal culture. In particular, whenever Colonisers came to learn of Matriarchy and (Black) Dalit emancipation, entire armies were sent to destroy them. So for self-protection all Sevaks, women and men alike, were trained in the martial arts and when travelling to unsafe Coloniser-controlled territory, people were armed for self-protection, and women had to cover their breasts for their own safety. Sevaks had a daily regime of practice at an Akhara (like a Japanese Dojo). This was mainly held outdoors, or in the communal open-walled thatched gazebo, and practice consisted primarily of meditation; as only the saint could be a warrior. Those selected to be Akaali (warriors), would guard the Dharamshalas and the Gurus and Sevaks on their travels, and were widely reputed as Earth defenders and emancipators of the downtrodden in the Colonised world. In 1699 when Khalsa was established, all initiated Sevaks were appointed as Akaali. As trained by the Gurus, Akaali warriors were great peacemakers first and foremost; hating violence, avoiding war, but always speaking truth to Power, and always ready to defend the sacred and oppressed- with their lives. It must be stressed that Dharamshala history is one of a sacred life in peace; violence was not glorified, and was rather seen as being a great tragedy, and battle only occurred briefly to defend against genocide, minimally and without vengeance (see Part 3). Rather than using violence to defeat violence, Dharamshalas dismantled Coloniser Patriarchy, and thus the actual source of violence itself.

Akhara

All the various aspects of this lifestyle and restored Indigenous culture (whether visible or less obvious- such as the rhythm of everyday life), were absolutely critical, interdependent, and implemented Original Wisdom. They were not merely a collation of interesting and colourful cultural practices and beliefs; each and every component was essential for the sacred symphony of Original culture to actually function correctly. Therefore undiluted and uncorrupted transmission of history, culture and Original Wisdom was key. This occurred through Indigenous ways of gaining and transmitting wisdom and knowledge; including Indigenous language, the oral tradition, hands-on work, art, spiritual dreaming, and communing with the Guru, ancestors and Elder Relatives (see also Chapter 4. Original Reality) through song and ceremony (including dance). Everyday activities such as preparing cuisine and weaving fabric, and living with sacred geometry, transmitted great sacred information. The oral tradition was a major part of life, from sacred teachings by Elders at ceremony, to storytelling of history and culture around the sacred Fire. Non-Indigenous academia (book learning, research and scholarship) was rejected by the Gurus as being inferior and useless.

Aad-Samvaad (sacred Indigenous song and ceremony) in particular were considered to be too sacred and confidential to write down or shared with outsiders, and were passed on orally by Elders in strict confidence to trusted Sevaks during special ceremonies. The Gurus had established Gurmukhi, an easy-to-learn phonetic script to record Gurbani for posterity, but Sevaks memorised it and the associated teachings were strictly passed on orally. Writing was otherwise hardly used by the common Sevak, and specific people were appointed to learn multiple foreign languages for sending letters or interacting with Colonial authorities. As described in Chapter 4, Indigenous language is Original instruction, and fundamentally determines thought and thus behaviour. Further to heavily modifying the local Sanskrit-derived languages with Indigenous words to make them functional, the Guru Matas worked respectfully with local Aboriginal tribes (or their spirits, if totally genocided) to restore Indigenous languages (e.g. Munda) in the regions where they belong. Children would learn these ancient Indigenous dialects as their mother tongue, to transition the Dharamshala away from the Coloniser’s languages entirely.

Newcomers to Dharamshalas were vetted thoroughly and once admitted as a resident Sevak, they were bound by certain vows as learners, and sworn to secrecy. This included the four basic commitments: to never to cut one’s hair (anywhere on the body), to respect all life as sacred (an ethical diet and lifestyle), to never consume intoxicants (alcohol, tobacco, drugs etc), and to treat the body as a sacred temple (including monogamous union and sex being sacred). Central to Gurmat is Nimrata (Deep Humbleness). Potential Sevaks were welcomed from any background, but those from the higher castes and classes, being very Egoistic, would typically have to spend entire lifetimes performing the most menial tasks to break their Egos as slow-learners, such as mucking out the horses (menial to their Colonised mind; all tasks were considered to be valuable). Thus few from such Egoistic backgrounds ever signed up or were failed to gain admittance, and so they comprised a small proportion of Sevaks. Instead, Dalits (former slaves with Indigenous ancestry) made up the vast majority (90%) of Dharamshala-resident Sevaks. Manifesting Nimrata for thousands of years; when the time came for the re-birth of Gurmat, they were readily entrusted by the Gurus, as Sevaks. Only the most committed and able Sevaks would later be initiated and trained as wisdom-carriers and eventual Elders.

There were profuse other aspects to the community’s thought process, behaviour, habits, practices and material culture, which cannot be described here. Suffice it to say that this life is difficult to imagine for a Colonised person today. This is the story of the Guru’s Dharamshalas and restoration of Indigenous culture. The lifestyle of Sevaks and material culture at the Guru’s Dharamshalas is Akaal Jeevan, a timeless natural existence as Originally intended, and is fundamentally incompatible with the Colonised world. And most importantly, this is a living story; most of the Dharamshala culture described above still survives in the remote Indigenous heartlands of Asia, Africa and the New World and Dharamshalas are being revived in all four directions, where life for Sevaks will virtually be the same, as it has been for thousands of years, in spite of the extreme pressures of the so-called ‘modern’ world (see Chapter 2. Becoming human with Original Wisdom (Gurmat, Guru, Sevak).

Next >> Chapter 1, Section 3 (Part 3). Khalsa Restoration and Challenges